This November is the one year anniversary of Slate, the small open source project I’ve been maintaining. It started off as a sort of toy project from my internship at TripIt, but now that real companies use it, I feel an obligation to keep it mostly bug-free. I hadn’t done much open source before, so this year has been a great learning experience for me! That said, there are a couple things I wish someone had told me a year ago.

Know Your Project’s Scope

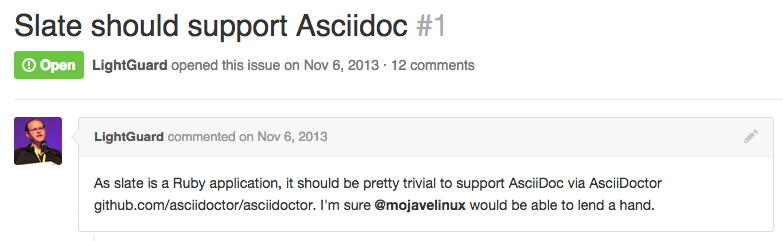

The first feature request I got for Slate was a request to add AsciiDoc support.

I fumbled it. I didn’t put in the effort to come up with a complete solution. Instead of a half-assed solution, I wish I had said “I don’t have time for this right now, but I’ll add it to the long term nice-to-have list.” A couple people have requested AsciiDoc support, but there are many more who are perfectly fine with Markdown. People who don’t need a feature don’t speak up about it.

Don’t be afraid to ignore feature suggestions and reject pull requests! I tried to please everyone when I started out, adding whatever people wanted, but I’ve found that features aren’t always appropriate. I think these are all good reasons to close a feature or pull request:

- The problem is in one of your project’s dependencies.1

- The project would not significantly benefit from having the feature, and adding it would increase the complexity of the code, or add edge-cases.

- The feature would be better as a plugin or extension of the project.

- The pull request complicates things, or has major problems with how it’s written.2

- You don’t have time or energy to implement it properly, and want to leave it as an open task for someone else to do. (In this case, I leave the issue open, perhaps with a “help-wanted” label.)

As the creator of your project, you’re the expert. That doesn’t mean to ignore suggestions…it just means to think carefully about what should be in your project, and what shouldn’t.

Communicate

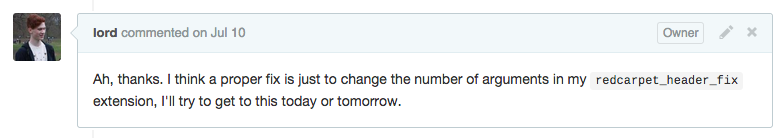

Keeping promises is difficult, especially when I’m trying to please bug reporters. I’ve been guilty of the “I’ll fix it this weekend” lie before.

I’ve seen some projects where the maintainer is going to “get to it this weekend” for about six months. It’s something I’m still working on — over-promising is pretty frustrating for others.

I don’t think I do this quite as much (or at least I try not to), but another annoyance for contributors is maintainers who don’t reply. I’ve submitted PRs for a number of projects, only to have them ignored for months and months. In my own projects, I try to at least acknowledge contributions as they come in, even to say “I’ll take a look at this when I have the chance, but I’m pretty busy.” If I no longer want to maintain a project, I’ll make it pretty clear in the readme that the project is unmaintained, so that contributors don’t expect a reply.

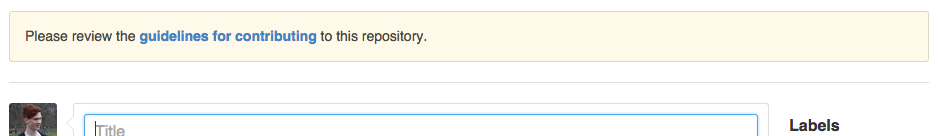

Another great way to help your contributors is to write a contributor’s guide. I didn’t actually know this until recently, but Github is nice enough to feature a link to your contributing.md prominently on the PR and issue creation pages. I’ve found that maybe ~80% of the people submitting pull requests for Slate actually read and follow the instructions, which is pretty good! In mine, I usually add a note that PRs should be pointed at the dev branch, and if you’re building out a big new feature, maybe to make an issue first to make sure we agree that the feature is in the scope of the project. It’s also a good place to list browser compatibility requirements.

Finally — be kind! Contributing to open source can be really scary, especially for people who haven’t done so before. A year ago, I was definitely scared to contribute myself. I was afraid of rejection. This is a real fear, but I think it can be reduced by maintainers who work with contributors to improve their code wherever possible, and thoroughly explain their decisions when they have to reject.

Grow Slowly

Large changes that take a long time to write are easy to burn out on, since you don’t have the satisfaction of completion every couple of weeks. This is especially true in a branch, because others will be submitting patches to master. Even if you conjure up the energy to finish your big new thing, merging will be…blegh. I try to build my projects incrementally whenever possible, and it’s been relatively successful so far.

As an aside, I’ve noticed this is similar to how many Github projects grow. Nobody really told me this, but I’ve noticed Github projects don’t gain all their popularity all at once. Slate has continued to gain usage at a relatively consistent rate over its life, as have some of my other projects. Repos aren’t like tweets or blog posts that receive all their traffic in a big burst.

In Summary

- Know Your Scope — feel free to reject pull requests and features if they don’t fit in with your project.

- Be Kind to Your Community — don’t over promise, acknowledge issues promptly, consider having a

contributing.md, and be kind! - Grow Slowly — build features incrementally, and remember that Github projects grow gradually.

These tips represent my subjective opinion from just a year of maintaining one project, and I definitely still have a lot to learn when it comes to maintaining projects. Nevertheless, if you’re starting your own Github project, hopefully you’ll be able to avoid some of the pitfalls I ran into.

With Slate, people would often report that header tags generated by Slate would sometimes have invalid IDs. This is a bug, but the bug lies within Redcarpet, not Slate. I created a workaround, and although we didn’t wait for Redcarpet to fix the bug, it also means there’s now a Redcarpet patch in Slate that I have to maintain. 2: When it came to pull requests, I used to have the attitude of “it has bugs? I’ll fix them for you!” I was worried about inconveniencing people who already put in the work to write a feature. I’ve since gotten more comfortable with asking pull requesters to make changes to their patches, even major, structural changes. It turns out most people are okay with polite criticism about their code!

...or for a change of pace, perhaps you'd enjoy my other blog Agoraphobia →