If you subscribe to many programming blogs, chances are you've come across a post describing someone's move off GitHub. They started as far back as the Microsoft acquisition in 2018, but they've increased in frequency recently. Both the Zig programming language and Leiningen build tool wrote about their move to other platforms late last year. I've drawn inspiration from these posts, and the countless similar posts from individual programmers. However, since they're mostly informational announcements telling people to update their repository URLs, they tend to only briefly mention the reasons the author chose to leave. They don't try too hard to convince a skeptical reader that perhaps they could leave GitHub too.

I'm going to migrate all my personal projects off of GitHub this weekend, in support of today's general strike in Minnesota. Instead of the traditional brief message, I'll instead try to record my thought process a little more deeply: my research into which groups have active protests of GitHub, why I think GitHub is a particularly suitable target, and what makes a boycott more or less effective. Migrating your open source projects off GitHub is obviously not the most radical, impactful action you could be taking right now, but also it's pretty easy! If you happen across this blog post, I hope you will consider it.

There are many groups protesting GitHub and Microsoft, but I'll discuss these four in this post:

- The "Give Up GitHub" campaign kicked off in 2022. The Software Freedom Conservatory (the non-profit that provides legal support for Wine, Inkscape, QEMU, Git, and many more free software projects) organized this . They cite how the GitHub platform itself is closed source software, instances of Copilot spitting out verbatim GPL code (a form of plagiarism), and fears over Microsoft's reorganization of all of GitHub under a "CoreAI" product division. They also point to GitHub's 2020 contracts with ICE, the controversial and violent immigration police here in the United States.

- The Free Software Foundation since at least 2024 have told the free software community to move projects off of GitHub to apply pressure on Microsoft, pointing again to Github's proprietary server code, as well as Microsoft's decision to require computers running Windows 11 to have a "Trusted Platform Module"; I'll let the FSF post explain why you might want to protest that.

- The Palestinian BDS National Committee upgraded Microsoft from a "pressure" target to a "priority" boycott target in 2025, describing Microsoft as "perhaps the most complicit tech company" in Israel's apartheid. BDS has already claimed two major wins here. In 2020, controversy forced Microsoft to divest its stake in AnyVision, a Israeli facial recognition startup used at checkpoints in the West Bank. Then, in 2025, Microsoft terminated Azure services for a subagency of the Israeli military called Unit 8200; this was right after a news article revealed they used Azure to process millions of intercepted phone call recordings from Palestinian civilians to determine where to fire lethal airstrikes in Gaza. BDS and the 2000+ Microsoft employees that signed No Azure For Apartheid, along with many other organizations (including a global network of MSFT-shareholding catholic nuns) continue to protest the Azure services Microsoft provides to the rest of the Israeli military.

- "ICE Out of My Wallet" launched in 2025, listing Microsoft as one of just seven top targets for a consumer boycott. Their goal is to put pressure on the $20M+ in Azure services Microsoft provides annually to ICE. (The official boycott currently just lists Microsoft devices as targets, not GitHub.) Back in 2019, there were also mass protests against GitHub's direct contracts with ICE to host their code; as far as I'm aware, they still host code for ICE today.

I've personally chosen to leave GitHub this weekend in support of today's general strike in Minnesota, and in protest of ICE's murder of Renée Good.

GitHub's weaknesses

I have four reasons why I want to specifically target GitHub in this post. First, for independent programmers, I think it's incredibly simple and straightforward to move your personal open source projects off of GitHub. Unlike quitting, say, Instagram or TikTok, which centralize and tightly control content discovery, the network effects keeping projects on GitHub are substantially weaker. When you quit Instagram, you become invisible; when you quit GitHub, you instead just add a small speed-bump for contributors. I also see particular ease when migrating a small project. Your small project has no CTO you need to convince, no 400-engineer monorepo, and no half-forgotten custom scripts calling GitHub's APIs, written by a coworker who quit a year ago. If your project depends on many strangers submitting drive-by pull requests, moving off GitHub will impose extra costs on you, and you may want to consider more carefully whether this is a cost you're willing to pay. But the vast majority of public repos — personal projects with few external contributors — will find leaving GitHub to be relatively frictionless.

Second, although you likely don't pay GitHub to host your open-source projects, they still make money from them! When my blog links to an open source project I've published GitHub, they don't just get to put their logo in front of some eyeballs for free; they also get my implicit endorsement, helping establish GitHub as the default choice for companies deciding where to put their internal repos and who to pay for LLM autocomplete. You might find this point kind of banal, but I really just want to emphasize it: by putting your personal projects on GitHub, you are providing them a valuable service! If your account is small, it may just be a tiny amount of value. But they find it valuable nonetheless, and I think this small amount of value matches the very small amount of effort it takes to move most of your code somewhere else.

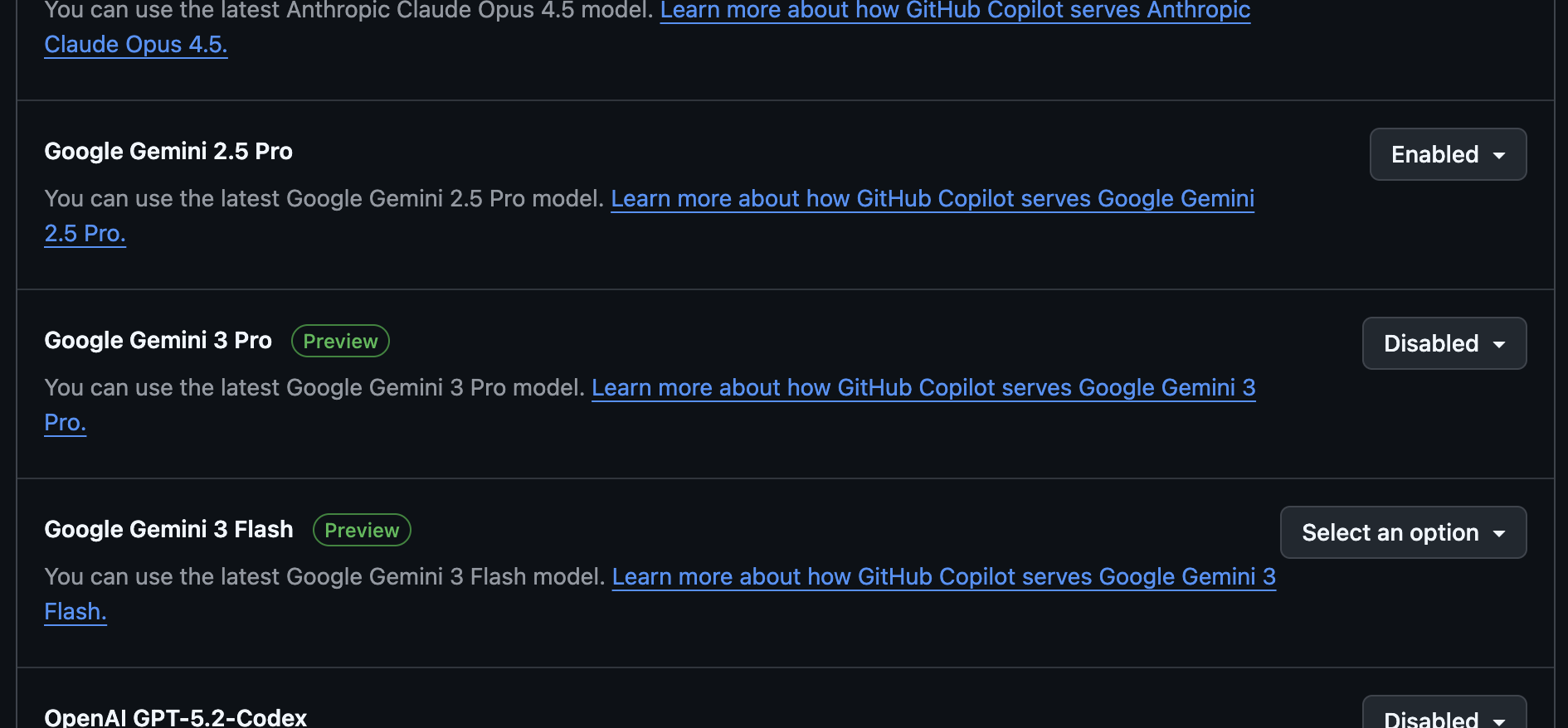

Third, GitHub's web interface has been in a steepening decline since the Microsoft acquisition in 2018, making it a less appealing place to put your code even without these ongoing protests. Why does an uncached page load of my repository's root take 2500ms, from New York City no less, with gigabit, 17ms ping internet? Why does GitHub Actions choose jobs to run "seemingly at random", causing Zig's CI to not even run on the main branch? Why does the settings page for enabling and disabling the 16 available LLM models take up two vertical laptop screens, and why, instead of a simple checkbox, does each dropdown have three possible states: "enabled", "disabled", and the mysterious "Select an option"?

Finally, I think open source communities, with roots in hacker culture from the 80s and 90s, form a particularly fertile soil for this sort of action. Many programmers contribute to open source projects for non-commercial reasons: out of a deep love for programming, or an ethical belief everyone should have the right to read and modify the code on their computer. Hackers also have a long history of general repulsion from Microsoft.

This history, however, is a double edged sword. As programmers, we are primed by this history to think individually instead of collectively. I have many friends who would agree with the causes above, and yet might resist participation in a GitHub protest. Even if you are someone who in general might join a boycott, once you hear that the plan is to convince a bunch of programmers — good luck, but clearly that plan won't work. Here, I think the choice of Microsoft is helpful, because I don't need to convince some critical mass of programmers. Instead, I get to play a tiny part in a large and global movement that already has momentum, made up of people who have never been burdened by the words "rebase merge conflict" before. I've chosen GitHub as a target so that my action mirrors the already-successful efforts of many others.

Some strategies are better than others

I have a vivid memory from a little over a decade ago, when I saw Richard Stallman speak about free software at an auditorium in lower Manhattan. In this speech, he cast as wide a net as he could, listing off the misdeeds of tech company after tech company and describing how we should stop using their products. (When one or two people in the audience quietly made their way to the exit — he had been talking long past the allotted time — he started castigating them for leaving before he was done.) His personal website today continues the tradition:

If my understanding of boycotts came from this speech, I would absolutely lean anti-boycott, but I'd like to convince you that there is another way! Boycott strategy makes a massive difference in efficacy. Stallman could learn a lot from the BDS National Committee, whose approach in turn was inspired by the highly visible South African anti-apartheid movement. Here's my own list of what has resonated with me:

- Don't protest everything all at once: We call it a "targeted boycott" for a reason. Target just a handful of companies with the most egregious violations, and in the common situation where you have complaints against all major vendors offering some service, don't boycott all of them. Make it easy for people to switch to an alternative, even if you're implicitly advocating for an imperfect company. Here, GitHub is a great target because many movements list Microsoft as a top target, and we have many free, open source alternatives.

- Build cross-movement coalitions: BDS chose Chevron as a priority target in part because many climate activist groups already have active protests against oil companies. The Software Freedom Conservatory chose GitHub as a primary target in part because anti-ICE activists protested it in 2020. When you boycott GitHub, you get to participate in several boycotts all at once.

- Cite specific, achievable goals: unfortunately free software boycotts sometimes have vague goals, like "stop discrediting the GPL". At other times, they cite specific goals that existentially threaten a company, like "release the source code to all of your software" or "only train your language models on public domain code." I think asking for Microsoft to cancel their contracts with the IDF and ICE are concrete goals, and Microsoft could do it without completely destroying itself.

- Protest publicly: I've seen some programmers delete their GitHub accounts silently, saying that their choice to leave is a personal one. I definitely can empathize with this sentiment — this feeling was hard for me to get over when writing this post. I feared it self-aggrandized what is truly a microscopic drop in the bucket. At the same time, I think there is incredible value to speaking publicly about why you're leaving, assuming it's safe for you to do so. In addition to this post, I also plan to not delete any repositories, instead replacing their contents with a README that explains my departure.

- Don't worry about perfection: I've seen some worry online that it's impossible to delete your GitHub account when there are still so many open source projects that use it. I agree! I plan to still use GitHub if I need it to contribute to other projects.

That's all I've got to say! What follows is some optional resources that you might find useful if you decide to make the move yourself. Thanks for reading this far, and if you're in Minnesota today, I hope you stay warm out there. ∎

Appendix A: Table of GitHub alternatives

| name | license | who is behind it | code review | is it objectively ugly | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centrally hosted (with self-hosting as an option) | |||||

| Codeberg/Forgejo | GPL | nonprofit based in Germany | branch-based | no | FOSS or noncommercial projects only; fork of gitea |

| SourceHut | AGPL | indie for-profit, not VC funded | git send-email | ugly (in a good way) | costs $4–12/month, financial aid available |

| Gitea | MIT | small startup, VC backed | branch-based | ugly (some parts) | weird vibes, and the free cloud hosting seems sort of like a demo instance; fork of Gogs |

| GitLab CE | MIT | publicly traded company | branch-based with stacking | just ugly | limited features for free accounts |

| Decentralized/federated | |||||

| Tangled | MIT | small startup, $300k+ in VC funding | patch-based with stacking | no | no private repos, built on ATProtocol |

| Radicle | MIT+Apache | some ethereum thing, $12M+ in VC funding | patch-based | no | private repos must be self-hosted |

| Self-hosted only | |||||

| j3 | GPL | i wrote it myself last week | no code review | i like to think not | barebones read-only web ui |

| Gerrit | Apache | patch-based with stacking | ugly | code hosting/review only; no issues, etc | |

| Gogs | MIT | single maintainer | branch-based | no | |

My personal take on these options: since these days my projects mostly don't have external contributors, I've chosen to move them to j3, a small local binary I wrote in Rust that lets you use an s3 bucket as a Git remote, and automatically pushes a read-only web UI to the bucket's index.html. If I had a startup that needed private code hosting, I would probably set up a Gerrit instance. If I was working on an open source project that wanted to make it easy for people in the open-source community to contribute, I would probably choose Codeberg, assuming I was not tempted by Tangled's code review workflow.

What is "patch-based" code review?

If you're familiar with GitHub's pull request workflow, you've done branch-based merges before. You prepare a branch with your changes, and then submit a pull request asking to merge your branch into

main. If somebody gives you feedback, you push additional commits on top of your base commit. In contrast, with the patch-based merge workflow originally popularized by Gerrit, you amend the existing commit and push it — something likegit commit --amend && git push --force. If you try this in GitHub, this would make the original commit you pushed disappear, but in patch-based review tools, your reviewers will instead see a diff from the original commit to the new one. In general, I'm trying to move towards patch-based workflows, since they work better with jiujutsu. "Stacking" here means it's easy to submit multiple pull requests for simultaneous code review, where each pull request builds upon the changes from the prior one in a chain. On GitHub, this is very difficult!

Appendix B: Migration bash scripts

To do the migration, I used the gh GitHub CLI (brew install gh && gh auth login on mac) extensively. To start, I cloned all my repos into three folders: migrate holds non-fork public repos, archive holds public forks, and private holds all private repos. The plan is to migrate public repos to a publicly visible host, migrate private repos to somewhere else, and archive most forks in-place on GitHub after adding a notice to the readme.

mkdir migrate archive private

(cd migrate &&

gh repo list --visibility public --source --json sshUrl --limit 10000 --jq '.[].sshUrl' |

xargs -I {} git clone {})

(cd archive &&

gh repo list --visibility public --fork --json sshUrl --limit 10000 --jq '.[].sshUrl' |

xargs -I {} git clone {})

(cd private &&

gh repo list --visibility private --json sshUrl --limit 10000 --jq '.[].sshUrl' |

xargs -I {} git clone {})

At this point, I sorted through the list of repos, moving any that needed individual attention out of these three folders. I also skimmed through the archive folder to see if there were any forks that deserved to be moved to migrate instead of just getting archived. This script prints which repos have external collaborators, which was useful here:

gh repo list --visibility public --json nameWithOwner --limit 10000 --jq '.[].nameWithOwner' |

xargs -I {} gh api "repos/{}/collaborators" --jq 'if length > 1 then "{}: \([.[].login] | join(", "))" else empty end'

Then, for every repo to migrate, I pushed all branches and tags to the new site. This script worked for my j3 remote, where pushing to a new remote implicitly creates a repo, but if you're uploading to codeberg or similar you'll need to change neworigin's url, and probably add a command to actually create the repo.

pushd migrate

for dir in $(ls); do

pushd $dir

git remote add neworigin j3://$ID_KEY:$ID_SECRET@$BUCKET_REMOTE/code/$dir

# per https://stackoverflow.com/a/59745167

git symbolic-ref --delete refs/remotes/origin/HEAD

git push neworigin --tags "refs/remotes/origin/*:refs/heads/*"

popd

done

popd

Finally, I replaced the repos on GitHub with a notice. I created a new migration-notice orphan

branch in the hope that this reduces the risk of downstream problems. I ran a similar script

on the archive directory; I decided to leave existing branches in-place there, since I wasn't

migrating them.

pushd migrate

for dir in $(ls); do

pushd $dir

# mark as unarchived if its archived rn, so we can add the notice

gh repo unarchive --yes

git switch --orphan migration-notice

cat > readme.md << EOF

I have chosen to migrate my projects off of GitHub until Microsoft terminates its contracts with ICE and

the IDF. A [read-only archive](https://code.lord.io/$dir/) of this repo is still available.

You can read more about my decision to leave on [my blog](https://lord.io/leaving-github/).

EOF

git add readme.md

git commit -m "add migration readme"

git push origin migration-notice

gh repo edit --default-branch migration-notice

# delete branches that aren't migration-notice

git branch -r | grep ' origin/' | grep -v 'migration-notice$' | grep -v HEAD | cut -d/ -f2- | xargs -I {} git push origin :heads/{}

# mark the repo as archived

gh repo archive --yes

popd

done

popd

Appendix C: GitHub stars and network effects

If you want people to discover your personal projects, you might say that GitHub stars, forks, and followers are a great way to enable this. While this is an interesting question, and I'm sure some people find these tools valuable, my personal experience has been that few people look at their GitHub feed, and this was before the Copilot prompt box pushed it further down the homepage. I've also heard it got diluted by LLM-generated bug reports, but honestly, I don't look at it any more.

To show one data point using star counts as a proxy for attention, I had a little over 700 followers in 2020, so while I wasn't one of the most followed users on GitHub, I still had more followers than the vast majority of GitHub users. Throughout 2020, I worked publicly on a Rust side project called Anchors, which by October had accrued a grand total of 4 stars. On November 9th, I published How to Recalculate a Spreadsheet, a tedious and technical blog post which discussed Anchors starting about 2000 words in. By the next day, Anchors jumped to 19 stars, and then (despite essentially zero code changes to the Anchors project itself) slowly climbed up to ~130 stars by late 2023. Clearly the blog post was the catalyst for these stars, and without it, Anchors would still have single digit stars today. That said, I can't prove to you that GitHub's feed didn't multiply the attention the repo got from the blog post. But at an average rate of 1 star every 10 days, and given the minimal stars the project had prior to the blog post, I guess it's hard for me to imagine GitHub's feed played a major role.

Assuming it's even your goal for your project to get discovered by others (for most of my projects it is not!) I think your side project will likely reach orders of magnitude more people on Bluesky, Twitter, or your personal blog than they will via GitHub. GitHub stars are a good sign of social proof, but I would argue they don't serve this role substantially better than stars on Codeberg.

Appendix D: Further reading

I've already mentioned Zig's and Leiningen's posts, but if you want to read what individual people have said about leaving GitHub, here is what I could find:

- Dave Gauer (2023)

- David Eisinger (2024)

- James Brind (2022)

- Kord Extensions (2025)

- Janik von Rotz (2025)

- Logan Connolly (2023)

- Macoy Madson (2022)

- Nicole Tietz-Sokolskaya (2022)

- Nils Norman Haukås (2024)

- Sam Thursfield (2025)

- Simon Tatham (2025)

- Tom Szilagyi (2024)

Appendix E: Richard Stallman, "A Free Digital Society" (New York, 2014)

...or for a change of pace, perhaps you'd enjoy my other blog Agoraphobia →